One of 50 stories, from 50 years of action

Driving into Ann Arbor, you may have noticed some of the beautiful farmland and natural areas surrounding the city. This “Greenbelt” didn’t always exist; it only came about after years of hard work and some bitter defeats. One such setback occurred election night, 1998: after five years of working to stop urban sprawl and prevent developers from turning natural areas and farms into subdivisions instead of developing in already urban areas, hundreds of volunteers, environmentalists, and members of various coalition groups eagerly awaited results of a vote on a massive ballot proposal that would do just that.

They had fought hard, building a huge coalition and mobilizing their neighbors. What’s more, it was a bipartisan effort, and who wouldn’t want to preserve natural features? Unfortunately, the coalition had found opponents in real estate developers, who had spent record amounts on advertising.

“We learned pretty quickly that a well-funded industry campaign can overwhelm the best ideas put forth by community leadership. We learned that next time we’d need to mobilize grassroots supporters to take on industry misinformation head-on,” said the Ecology Center Director Mike Garfield. Despite the coalition’s best efforts, the proposal didn’t pass.

But the Ecology Center didn’t give up on a vision of a region where it was still possible to support farming and grow food in proximity to the city and experience intact forests a short ride away, rather than a region defined by endless suburban sprawl.

Source: "Grassroots Victory Sets National Precedent" by Ted Sylvester, January/February 2004 issue, From the Ground Up, The Ecology Center

The stakes of stopping sprawl

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Washtenaw County and Southeast Michigan was one of the fastest growing locales, not only in the state, but in the entire country. Because Michigan law allows local governments greater control over development and land use than other states, there were more planning jurisdictions than anywhere else in the country. This decentralized control led to chaotic development plans and rampant sprawl.

It didn’t help that land use has always been a political hot-button issue. Sprawl in Southeast Michigan, specifically, is tied to economic concerns, farmland and natural area preservation, and social and racial issues. In developing rural and suburban areas, cities with existing infrastructure to support new development can get left behind. Social justice advocates worried that the suburbanization of the region would “hollow out the urban areas of Southeast Michigan even worse than they already had been,” said Garfield.

And it wasn’t just urban areas at risk: the development proposals put forth in the early 90s looked to effectively build entire cities out of farmland near Ann Arbor, with 5,000 to 10,000 proposed units in Whitmore Lake and Pittsfield Township. Residents worried about suburbanization and how their lives would be altered, and environmentalists worried about the loss of natural features and farmland for a local food supply.

Building coalitions, Proposal B

The Ecology Center felt it had to get involved, and that problems of regional planning were too big for local legislation alone. They’d have to work up to the state, where policies could incentivize investments in urban areas and create other measures to control development.

“When we did our assessment of Michigan law and what was really possible at the local level, we came to the conclusion that a regulatory approach wasn’t going to work very well, that there weren’t any really good fixes without changing state law; and we also thought at that time that changing state law was a long way off,” said Garfield, “so the solution we came up with was to promote land preservation through purchase of development rights initiatives, where easements are acquired from farm property owners that are held by a unit of government or some nonprofit, and land stays in private hands.”

Purchase of development rights (PDR) initiatives involve financially compensating farm or land owners if they agree to not develop their land. The farmers and landowners still keep the land and can use it for approved purposes, like farming, but the land can’t be used for housing developments or strip malls. By the time the Ecology Center was thinking about PDR programs, other locales had already had some success. In 1994, a PDR program was created in Traverse City to preserve cherry orchards. This maintained the cherry crop, thus boosting the economy and ensuring that much of the land’s beautiful natural features would be protected.

The Ecology Center and its partners knew that a PDR initiative could work on a township level, and that maybe they could get an initiative passed on a county level, with the eventual goal of having a state-level program. The Ecology Center worked with the Sierra Club, Michigan Environmental Council, and other organizations to draft and promote a PDR program for Washtenaw County.

In 1996, the Washtenaw County Board of Commissioners appointed a task force to research land use conservation tactics and came to the same conclusion as the environmentalists: a PDR initiative was the best way to preserve farmland.

The result of this inquiry and the groups’ advocacy was Proposal B. This countywide ballot measure was a land use reform omnibus that sought to raise tax money to buy the development rights of farms and ensure “smart growth” through additional measures.

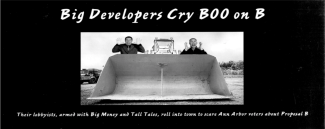

The Ecology Center and partners knew this would be a contentious issue given what was at stake. What they didn’t anticipate was that this would be the most heated ballot campaign in the county’s history, incurring them the wrath of the Washtenaw County Homebuilders’ Association and the realtors’ association. The Ecology Center’s opponents saw Proposal B as a test case and were (rightly) worried that its passage could lead to a domino effect of PDR programs across the state. They were willing to dig into their deep pockets and poured a whopping $250,000 into ads, many of them on television, the first to ever be run in Washtenaw County for a local political campaign.

“We were shocked,” said Garfield, “and we were even more surprised when we saw the ads.” The homebuilders’ and realtors’ associations argued that the farmland proposal was bad for farmers and used actors playing farmers to convince voters. Although the Ecology Center had assembled one of the largest grassroots campaigns in county history with over 500 volunteers, and although there was a broad coalition of farmers, business leaders, Republican community activists, and prominent conservative voices passionate about farmland preservation supporting Proposal B, they couldn’t compete with the Homebuilders’ ads; the proposal only received 42% of the vote on election night, 1998.

Lost the battle, won the war

“We kept trying to figure out how to make some good out of this bad defeat. We decided that we’d try to work on smaller parts of the proposal first,” said Garfield.

Remaining locally-based groups -- including the Ecology Center and the local chapters of the Sierra Club and the Farm Bureau -- continued to meet and regroup, working to learn from the loss and come back stronger. They knew they’d have to start small, and, instead of taking a comprehensive approach, they’d build back up slowly. In 1999, the coalition ran a citizens’ initiative to save natural areas in Ann Arbor. They circulated petitions that called for a ballot referendum and collected over 7,000 signatures before winning in a landslide vote.

In 2000, the proposal went back to the county ballot. Saving natural areas was an uncontroversial issue, and the coalition was gaining steam. The Potawatomi Land Trust (now Legacy Land Conservancy) and Huron River Watershed Council joined as active members of the proposal campaign, and together the organizations approached the realtors and the homebuilders to ask if they would consider joining on. After several difficult and intense meetings, the realtors signed on before the measure made it to the ballot. The homebuilders were more hesitant but eventually endorsed the proposal a week before the election. The proposal passed with overwhelming support.

The coalition had saved some natural areas, but there was still the issue of preserving farmland. And after their two successes, they knew they had a chance, though preserving farmland was not as broadly popular as saving natural areas. In 2003, the coalition developed a proposal to save farmland in townships and encourage development back into urban areas.

The Open Space and Parkland Preservation Millage (“Greenbelt”) would ask residents of Ann Arbor to tax themselves in order to set up a PDR for land outside of the taxed region. In some ways this was a strange proposal, to ask community members to tax themselves in order to protect land outside of their borders, but the Ecology Center believed that the land was close the community would embrace it.

This was an innovative albeit controversial solution and brought up tensions from the 1998 campaign. But with the Potawatomi Land Trust, Huron Watershed Council, and Sierra Club as primary collaborators, the Ecology Center was ready. Equipped with the lessons they had learned from Proposal B’s defeat, they raised money in anticipation of negative television ads and put out messaging of their own.

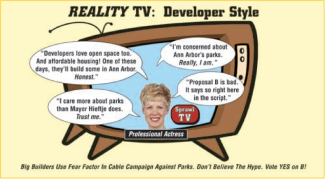

The coalition’s ads showed how their opponents had self-serving interests in blocking the proposal.

“When the Home Builders’ ads came out, this time they didn’t say we’d be bad for farmers, but for parks and schools,” said Garfield. “We argued instead that they were trying to fool Ann Arbor voters, and countered with our own messages that said ‘those ads you’re seeing on TV are not about parks and schools; this proposal will be good for schools. That ad is from the Home Builders’ Association, and here are the facts.’ We tried to have fun with it.”

The message was getting out, and Mayor John Hieftje, prominent members of the business sector, the Ann Arbor Chamber of Commerce, and real estate companies joined the Ecology Center to advocate for the Greenbelt.

Five years after the coalition’s tough loss, and ten years after beginning to work on the issue, the Greenbelt ballot proposal passed with a whopping 67% of the vote. And even better, the campaigns had created an infrastructure for preserving natural areas and farmland in Washtenaw County. In 2004 and 2005, similar proposals passed in Scio Township and Webster Township, respectively.

The Ecology Center’s vision from the early 1990s has come to pass. Over 6,300 acres of working farmland and open space has been preserved through the Greenbelt program, including 28 miles of rivers and streams, 11 new public nature preserves, 1,476 acres of wetland, and 1,341 acres of forest. The greenbelt has made farming more accessible and preserved waterways and biodiversity. When you combine it with the Washtenaw natural areas program and other local initiatives, over 10,000 acres of land has been saved. And this isn’t the end: the program provided 30 years of funding, so more land is being preserved to this day.

“Today Washtenaw County has one of the most vibrant local food movements in the Midwest, with towns, farms, and green space a short drive from one another” Garfield said. “That’s only the case because this community came together in the early 2000s to fight powerful financial interests and make sure it would be that way.”