Caulk and weatherstripping may not sound as glamorous as high-tech clean energy solutions, but straightforward, cost-effective energy efficiency measures are essential to solving the climate crisis before it’s too late. Studies have shown that energy efficiency measures alone can cut U.S. energy use and greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2050, with building improvements such as weatherization delivering 40% of that reduction.

The Ecology Center has been demonstrating the viability of these simple solutions since the 1970s, with a focus on expanding their accessibility across the income spectrum. Low-income households have borne disproportionate energy costs and pollution-related health harms for decades, and making weatherization accessible to low-income families remains a matter of environmental, economic, and racial justice.

The Collapse of Cheap Energy and the Rise of Energy Efficiency

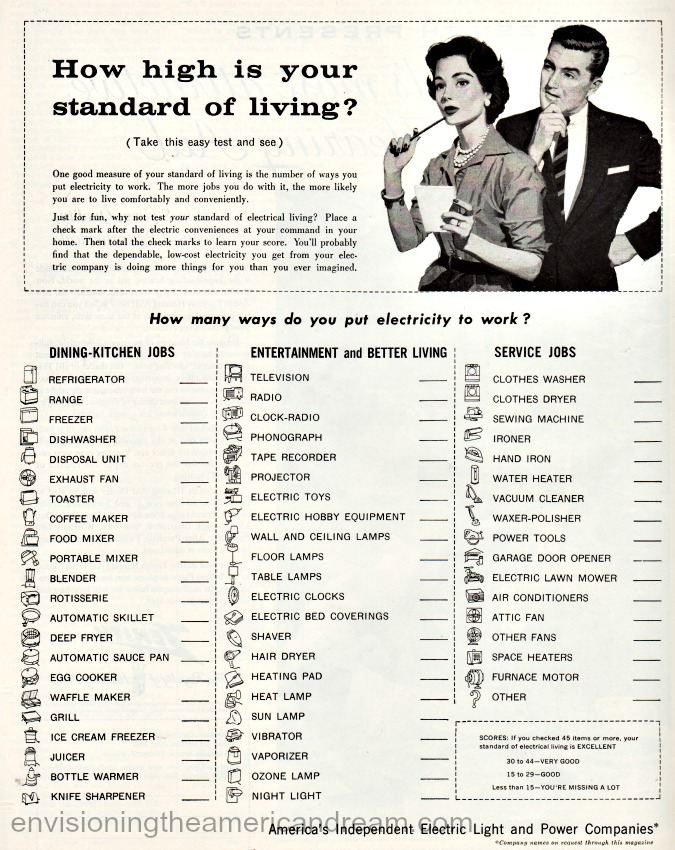

When the Ecology Center began working on energy issues in the early 1970s, energy conservation ideas and energy efficiency measures were only beginning to gain broad traction. States now require utilities to provide energy efficiency services and we’ve become used to seeing utility companies promoting them, but throughout most of the twentieth century, utilities aggressively pushed customers to increase energy use. Thanks to the Texas oil boom of the 40s and 50s and Americans’ post-WWII prosperity, home comfort through cheap energy wasn’t a hard sell. Utilities sold it hard nonetheless, with advertising and financial incentives for increased use. Millions of homes started whirring with newfangled air conditioners and other appliances. Summer electric usage first surpassed the energy demand of winter heating in the United States in 1957, just one year after the kickoff of the massive “Live Better Electrically” campaign, supported by 300 electric utilities and 180 electrical manufacturers and represented on television by then-actor Ronald Reagan, host of General Electric Theater.

Fifteen years later, the bubble burst. The 1973-4 oil embargo and U.S. oil crisis drastically altered Americans’ energy consumption calculus by creating a staggering surge in energy costs. The crisis spurred dramatic governmental action to reduce U.S. dependence on foreign oil, and it provided a major opportunity for environmentalists to advance energy conservation at the national level.

The rise of home weatherization represented one of the earliest and most successful measures to introduce Americans to conservation ideals and to reduce fossil fuel usage long-term, and economic accessibility was a consideration from the beginning. The federal Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) was established in 1976 to provide low-income families with financial and technical assistance needed to weatherize their homes, preceding the establishment of the U.S. Department of Energy in 1977 and the establishment of the first national energy efficiency standards for home appliances in 1978.

Making Energy Efficiency Accessible: Home Energy Works

Working on the cutting edge of the energy conservation movement, the Ecology Center sought to make energy efficiency accessible to all when, in 1977, we began offering free workshops on home energy conservation.

The workshops, supported by an Ann Arbor Community Development Block Grant and coordinated with assistance from local architecture firm Sunstructures, Inc., showed participants how to weatherstrip doors and windows, how to save on gas and electric bills, and what to look for when buying insulation. Over the next three years, Ecology Center staff educated hundreds of participants through neighborhood workshops across Ann Arbor. However, these workshops weren’t consistently reaching many of the people most affected by high energy costs: low-income residents, people of color, and senior citizens.

To better engage these constituencies, the Ecology Center transitioned in 1981 from its energy conservation workshops to a more personalized approach through home weatherization visits, a model that had been successful in other states. The Home Energy Works visits offered much more specific advice, technical assistance, and do-it-yourself training than traditional energy audits, and hands-on education was a central element of each home visit.

Former Ecology Center staff member Jim Frey discusses how collaboration with the City of Ann Arbor shaped the home energy visit program and helped build a culture of conservation.

Recalling the home energy audits she conducted during the early days of Ecology Center’s Home Energy Works program, Hildie Lipson says that Ecology Center staff would use comparisons to help people understand energy waste, energy efficiency, and the financial benefits of weatherizing their homes. Envisioning a basketball-sized hole in the living room wall, for example, could allow a client to visualize the total impact of small unsealed gaps and poorly insulated surfaces in their home.

Clients regularly reported major cost and energy savings, often reducing heating bills by as much as 20%. A few went even further. Lipson remembers one woman, a local artist, who was so passionately motivated after her consultation that she sealed off every crack and leak she could find, implemented lifestyle adjustments with gusto, and ultimately reduced her energy use so drastically that her utility company called to make sure she still lived in her home.

Going Public: Nonprofit Energy Works

The Ecology Center extended the successful energy services program in 1985 to include low-cost services for residences and businesses not eligible for free services, in part to secure the future of free Home Energy Works for low-income residences in the face of expiring grant funding.

In 1988, Ecology Center was able to expand Energy Works again. The new Nonprofit Energy Works program reached out to 3,500 nonprofit organizations across the region with help to save as much as 30% on energy bills--money that could then go directly toward services instead of toward overhead utility costs. Most nonprofits, running on tight budgets and investing as much as possible in their missions, had never received a technical audit because of the $1,200 to $1,500 cost for a typical 10,000 square-foot facility, despite the potential for long-term cost savings.

Housed for a time in Ecology Center’s education space at the Leslie Science Center and run by Aileen Gow, Nonprofit Energy Works provided onsite services similar to the Home Energy Works residential visits, as well as support for education and funding. Ecology Center ran energy conservation workshops at sites such as the UAW headquarters, educated organizations through the Nonprofit Energy News newsletter, and worked with Michigan Consolidated Gas Company and Detroit Edison to help nonprofit organizations obtain significantly discounted or free technical energy audits.

The nonprofit program helped expand the community reach of energy conservation, and so did a shift for the Home Energy Works program. In the mid-1990s, the Ecology Center was able to secure the long-term future of local home weatherization services by persuading the City of Ann Arbor to adopt responsibility for the program as a public service. Since 2009, Washtenaw County has run the weatherization assistance program that the Ecology Center pioneered here in the 70s.

Low Income Weatherization and Energy Justice Today

Ecology Center’s energy work has addressed inequity from the beginning, but the approach has both broadened and sharpened since the 1970s. Work targeting the energy crisis and promoting energy conservation and affordability for all has shifted to address the climate crisis and to approach accessibility with a focus on environmental racism as well as economic injustice.

The fight for what University of Michigan researcher and Ecology Center board member Tony Reames calls “energy justice” is one of Ecology Center’s continued areas of focus in its current energy program work. Lack of access to home weatherization remains one of the many faces of environmental racism and economic injustice in America today, as it was in the 1970s. Even before the economic ravages of Covid, ⅓ of American households were already struggling to pay their energy bills and to stay safe and cool during heat waves like the current one.

Although energy efficiency practices are now widespread, they remain far from ubiquitous. Cost often puts weatherization upgrades out of range for low-income homeowners, and landlords have little incentive to invest in the improvements when renters pay the energy bills. As a result, poor people often pay a much higher proportion of their income on energy expenses than their more affluent neighbors. The American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy documented the high energy burden on low income households in 2016, finding that “On average, low-income households pay 7.2 percent of household income on utilities—more than twice as much as the median household and three times as much as higher income households.”

Despite this dramatic inequity, both public and private energy efficiency initiatives still leave many families in the lurch. The Consortium for Energy Efficiency found that, as of 2015, only 6 percent ($350 million) of U.S. electric energy efficiency spending was dedicated to low-income programs. This represents a major unmet need, with more than 36 million U.S. households with incomes below twice the federal poverty level ($49,200 for a family of four) using more than 30 percent of U.S. residential electricity and comprising 27 percent of U.S. households.

In addition to bearing the cost of high energy bills, low-income households also bear the brunt of health effects produced and worsened lower air quality and exposure to temperature extremes. Energy efficiency has been proven to have direct health benefits, not only by reducing overall emissions and outdoor pollution from power generation, but also by improving indoor air quality in the built environment and protecting residents from extreme temperature variations that can exacerbate respiratory illness. Communities of color are disproportionately affected.

At the beginning of March 2020, the Michigan Public Service Commission approved settlements with the state’s two largest energy utilities, DTE Energy and Consumers Energy, to expand the benefits of energy waste reduction by improving affordability for low-income households. The Ecology Center participated in both settlements. Policy Director Alexis Blizman provided expert testimony demonstrating the importance of implementing home health and safety improvements alongside energy efficiency measures, providing best practices for joint health and safety and energy efficiency programs in low-income households, and recommending specific adjustments to the utilities’ proposed plans to better meet the needs of low-income single family and multifamily customers.

The Ecology Center has been arguing for nearly 50 years that energy conservation needs to be accessible to all. It remains now, as then, a matter justice and our collective wellbeing.

Keep an eye out for future stories on Ecology Center’s other related work, including running the Michigan Renewable Schools Program to educate the next generation on energy issues, advocating for state energy policies prioritizing sustainability and justice, and promoting green affordable housing development and renovation.

Research for these stories provided by the Environmental Justice HistoryLab at the University of Michigan. For more details, check out our history archive.