Art and community science project puts the focus on plastics and microplastics in our watersheds

On a blustery April morning, the Ecology Center Healthy Stuff team gathered with Sidewalk Detroit and about 60 people in Detroit’s Eliza Howell Park to collect garbage from the Rouge River. Some in the group donned waders and ventured into the water, while others formed a bucket brigade to carry the trash to a third group waiting with garbage bags to sort into piles of plastic, metal, rubber and styrofoam.

Detroit-based artist Halima Afi Cassells stood between multiple trash cans calling out directions for where each material should go. The groups collected and sorted for hours and by the end of the afternoon the fish and other aquatic wildlife in that part of the Rouge were likely a little happier and a little less encumbered by all that trash.

But while cleaning up the river was a worthy project, it wasn’t the only purpose of gathering that day.

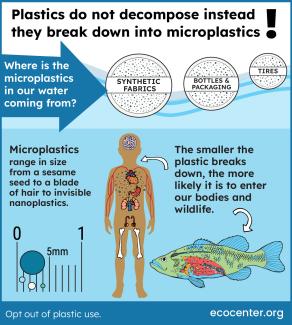

Much of the trash pulled from the river was plastic. All kinds of plastic bottles, lighters, styrofoam cups, and even a giant yellow exercise ball. And because plastic does not decompose like natural material, it likely wasn’t going anywhere for a very very long time. In fact, less than 10% of all plastic is recycled. Most plastic just breaks down into tiny particles called microplastics and nanoplastics. Those microplastics can enter the bodies of fish and even humans, and research has shown that microplastics may be linked to endocrine disruption, increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases and contribute to other health problems. Many of the chemicals used to make plastic are toxic to humans and the environment.

The cleanup day was part of a larger project bridging art and citizen science to raise public awareness about the dangers of plastic in our watersheds and throughout the entire plastic lifecycle. In partnership with Sidewalk Detroit and Halima Cassells, the Ecology Center organized a series of hands-on workshops after the cleanup day. These workshops gave Detroit youth and adults opportunities to help Halima create a semi-permanent art installation made from upcycled plastic found in the river.

The workshops mixed scientific and creative inquiry about the plastic problem and solutions. While Halima worked with workshop participants to create pieces for the installation, the Ecology Center staff and summer interns busted out our water filters and microscopes. Our team worked with youth participants to pump water through a paper filter that trapped microplastics - too tiny to see with the naked eye. Once the paper filter was placed under the microscope tiny colorful plastic threads appeared on the paper.

These tiny threads that accumulate in our river water are a result of plastic’s toxic lifecycle. Microplastics largely come from deteriorating products such as synthetic fabrics, tires and bottles and packaging. Just one fleece jacket sheds up to 250,000 microfibers during a single wash. “Fast fashion” depends on polyester which does not easily degrade and releases synthetic microfibers when washed. Most washing machines don’t catch these synthetic microfibers before the water flows to the wastewater treatment plant and flow into our local watersheds.

Our Great Lakes see 22 million pounds of plastic every year, and at every stage of plastic’s lifecycle - from manufacturing, to use, to disposal - microplastics are created. The smaller the plastic breaks down the more likely it will leach into our bodies and wildlife.

To address the plastic crisis we need bold commitments and the resources to make change at the institutional, municipal, state, and national levels. You can support policies that reduce plastic pollution, like banning plastic bags and holding producers responsible to clean up pollution.

The Ecology Center recommends a set of actions for the Michigan Legislature.

These include:

- Rejecting false solutions to plastic pollution (like chemical recycling)

- Restricting single-use plastic

- Phasing out the most dangerous plastics

- Updating our state’s Bottle Bill

- Creating an Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) law

The Ecology Center is advocating for Michigan policies that will address microplastics in several important areas. These policies would ban microbeads into waters, regulate pre-production plastic pellets, test and develop comprehensive plans for microplastics, and require all new washing machines to contain synthetic fiber filter systems.

When the workshop participants peered into the microscope they saw the microplastic threads. Our Ecology Center Healthy Stuff team guided youth and adult participants to think about where these plastics come from, and why they might be in the Rouge river. We even gave them lint rollers to use on their clothes, then put the lint under the microscope. We showed them plastic water bottles and face wash that contained plastic microbeads.

Almost four months after we collected trash from the Rouge River, a semi-permanent structure made from plastic bottles and other plastic materials arched over the trail down to the river. Ironically, the archway was beautiful as colorful plastic pieces shaped into flowers intertwined with tree branches. But was it beautiful? Halima had used the structure to raise critical questions about how plastic pollution can impact our natural world. The solution has to be more than just cleaning up the river; it’s about understanding the true environmental and human health costs of producing, using and disposing of plastic.

The choices you make are also part of the solution. Here’s some tips to get you started:

- Find reusable alternatives to single-use plastics like plastic bags, straws, plastic bottles, cups, and plastic packaging.

- Choose natural fabrics over synthetics, and think about how much your clothes need to be washed

- Recycle plastic labeled #1 and #2 and check your local recycling facility to see what other kinds of plastic they may accept

Learn More:

- Honoring Water and Reimagining Waste with Halima Afi Cassells: Black Her Stories Podcast

- Michigan Microplastics

- Alliance for the Great Lakes: Great Lakes Plastic Pollution

- Wayne State: Smart Management of Microplastic Pollution in the Great Lakes

- Recycle Ann Arbor: Plastics Explained