How Michigan Wrote the Playbook for Trump’s Federal Rollbacks

By: Lily Antor and Elizabeth Harlow

As Governor of Michigan from 1991 to 2003, John Engler largely dismantled what had been some of the most effective environmental protection policies implemented in the U.S. He undermined government agencies, implemented large-scale legal rollbacks, and gave favors to big business that left Michigan dirtier and sicker. These strategies helped shape the Republican party’s current national playbook for anti-environmental action today. We have stories to share about the Ecology Center’s resistance to these attacks in weeks to come, but this story, published just one week ahead of the 2020 election, focuses on the enduring consequences of anti-environmentalists using political power to undermine public health.

“Paramount public concern”: Michigan’s Early Bipartisan Leadership in Environmental Politics

Since 1963, Michigan’s state constitution has included an environmental protection clause. Article IV, Section 52 proclaims that “The conservation and development of the natural resources of the state are hereby declared to be of paramount public concern in the interest of the health, safety and general welfare of the people. The legislature shall provide for the protection of the air, water and other natural resources of the state from pollution, impairment and destruction.” This move to legally enshrine environmental protection as a core state value and priority was a pioneering one: a wave of other states followed in the early 1970s, and today roughly half of U.S. state constitutions include a similar clause.

This history offers a critical reminder that environmental action hasn’t always been a polarized political issue, championed by Democrats and fought by Republicans. Into the 1980s, support for environmental cleanup and protection was widespread and bipartisan. Federally, the EPA was established by an executive order from Richard Nixon in 1970. And throughout the '70s and '80s, Michigan enacted and enforced some of the most robust environmental protection laws in the country, regularly holding polluters to a higher standard of accountability than federal requirements permitted. Most were enacted under the leadership of long-serving Republican Governor William Milliken.

John Engler Spearheads New GOP Deregulation Playbook in Michigan

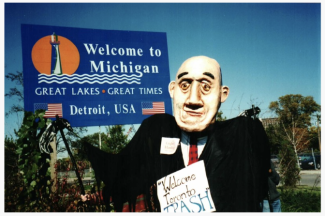

When Republican John Engler was elected as the 46th Governor of Michigan in 1990, he was not merely uninterested in environmental protection: he was actively hostile to it. In twelve years, his administration successfully tore at the foundation Michigan had developed over the previous thirty years to protect the health of its people and the sustainability of its resources.

Engler’s unprecedented success in enacting environmental rollbacks across his three terms provided a model for what has now become textbook GOP deregulation strategy everywhere. Engler dismantled staffing and public oversight of environmental agencies. He rolled back the state's environmental clean-up standards. And, he regularly prioritized corporate profits over Michiganders’ wellbeing, providing tax breaks, unwarranted permits, and other favors to big business at the expense of public health.

While Engler’s gubernatorial tenure was marked by a plethora of spending reductions and the implementation of 31 different tax cuts that reduced the capacity of state government to provide for Michigan’s people, Engler’s environmental policies were among his most enduring and egregious harms. His influence endures today as Michigan residents continue to deal with the long-term economic and health impacts of his policies and the further deregulation they inspired, including the outrageous application of a now well-honed playbook by the Trump administration, which has rolled back nearly 100 environmental protections, declined to prosecute environmental crime, and attempted to reduce the EPA to “little tidbits.”

The environmental community, including the Ecology Center, fought long and hard to prevent the dismantling of our state’s historically strong environmental regulations, but the Engler administration was largely successful in decimating Michigan’s leadership position in environmental protection.

Administrative Reorganization with an Aim to Maim

John Engler succeeded in wreaking long-term, comprehensive harm on Michigan environmental policy in large part by consolidating executive power over it. In 1995, he issued an executive order that transitioned environmental responsibilities formerly held by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR) to the newly-formed Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ). He then moved jurisdiction over environment-related public health issues from the Michigan Department of Public Health to MDEQ.

Engler placed at MDEQ’s helm Russell Harding, an anti-environmental political operative guided by a belief that “environmental regulation has been a serious impediment to job creation in the state.” Harding was installed without a single public hearing, and the new MDEQ had no public oversight commission. Michigan’s legendary Attorney General at the time, Frank Kelley, denounced Harding for immediately “selling out our environmental laws to the special interests” and “violating his constitutional duty” under Article IV, Section 52 and called for Harding’s resignation just months into his tenure.

The new Harding-led MDEQ anchored Engler’s strategy to increase executive control over environmental policy. He used that control to not only to make policies more lenient to polluters, but also to minimize enforcement of the policies that remained intact. Harding implemented budget cuts and changes to culture and mission that drove away disgusted and demoralized former-DNR staff, who went unreplaced. Institutional knowledge accumulated over years of work was lost, and staffing ran thin. By 1996, one anonymous remaining staff member reported to Dave Dempsey, then policy director of the Michigan Environmental Council, that “Staffing levels in the field are becoming so low that our ability to stop illegal activities is minimal at best. The morale in the DEQ is lower than I have ever seen it.”

The broken agency has remained a partisan battleground in state government ever since. Jennifer Granholm attempted to reunite the DEQ and DNR in her last year in office; Rick Snyder promptly split them again. In 2019, Governor Gretchen Whitmer acted to amend the damage and move forward by restructuring the Department of Environmental Quality as the Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE). The newly established EGLE specifically added offices aimed at addressing clean water advocacy and elevating long neglected issues of environmental justice.

Engler’s attack on administrative structure allowed an unraveling of environmental protections and real harm to the environment that could not be rebuilt quickly, easily, or even fully after he left office. The MDEQ’s deliberately engineered dysfunction has affected nearly every aspect of the state’s response to environmental issues for twenty-five years, and efforts to rebuild the system continue.

The Polluter (No Longer) Pay Rollback

In addition to crippling the state’s environmental agencies, John Engler’s administration also left a pernicious legislative legacy of corporate favoritism that continues to impede Michigan’s pollution clean-up efforts today.

Shortly before Engler took office, Michigan had enacted strongest-in-the-nation "Polluter Pay" legislation, requiring companies to take accountability for adequately cleaning up contamination sites that they were responsible for creating. The law was a resounding environmental success. In its first four years, it recovered $35 million from culpable corporations to support the clean-up of dangerously polluted land and water at over 3,200 sites.

In 1995, Engler led rollbacks that took the teeth out of the law's liability provisions and gutted the clean-up standards, leaving Michiganders near polluted sites at ten times higher risk of cancer and other illnesses. An Ecology Center newsletter early that year noted that the repeals weren’t based in any scientific rationale: it had recently “become fashionable to suggest that the risks posed by environmental contamination sites are really very small, and that efforts to clean them up have been too costly relative to the risk period” despite the fact that mounting scientific evidence showed greater danger, not less, to public health than had previously been understood a decade prior.

The "fashionableness" of the idea that pollution wasn't so bad was limited mostly to a small faction. Engler and the legislature rammed the rollback through despite the fact that the polluter pay law was overwhelmingly popular with Michigan voters across the political spectrum. 85% of people surveyed by independent polling firm EPIC/MRA in April 1995 supported it. The same poll found that only 14% thought that Michigan's environmental laws in general were too tough, while 46% said they didn't go far enough.

Cleanup of contaminated sites still remains inadequate, as Michiganders are periodically reminded, like when “green ooze” started seeping onto I-696 in late 2019 from an old, partially mitigated site. Just last year, State Senator Jeff Irwin and Representative Yousef Rabhi introduced twin bills in the Michigan House and Senate to restore polluter pay standards, citing long-known problems like the still-expanding Gelman Sciences 1,4 dioxane plume beneath Ann Arbor and new ones, including more than 11,300 estimated PFAS-contaminated sites in Michigan.

Michigan Becomes a National Leader...as a Dumping Ground

By at least one metric, Michigan is the trashiest place in the country: it has a higher volume of buried waste per capita than any other state in the U.S., with a whopping 62.4 tons per person of trash permanently buried here according to 2019 EPA data. To picture just how much waste that is, imagine four eighteen-wheeler trucks full of garbage parked outside of every home in the state.

A lot of that garbage has been trucked here from elsewhere thanks to John Engler, who led efforts to actively welcome solid waste from out of state. Under Engler’s tenure, the legislature lowered the bar on landfill requirements and disempowered state and county regulators to exercise oversight on waste flow, and the MDEQ granted new permits for much more landfill space than Michigan needed. Engler’s administration also funded new landfill construction with taxpayer dollars, using the Michigan Strategic Fund to underwrite at least $122 million in tax-free bonds to national and international corporations like Waste Management.

The waste industry lubricated the wheels for this policy backslide, contributing nearly $200,000 to state legislators in the 1996 campaign cycle alone, with industry PACs successfully targeting key leaders of both political parties. It was money well spent for the corporations, who benefited from a new oversupply of landfill space that made dumping in Michigan cheap: by 1997, Michigan’s landfill tipping fees ranged from 25% less expensive to as much as 200% less expensive than neighboring U.S. states and Canadian provinces.

Though Michigan has made progress in curbing the tide of imported waste in the last decade, the state remains an appealing, artificially inexpensive dumping ground today because of continued oversupply of landfill space and a low state tax on landfill use rights. It receives trash from ten other U.S. states as well as Canada, and nearly a quarter of the garbage that was dumped in Michigan last year wasn’t generated by Michiganders.

Energy Company Profits, at High Public Cost

In the 1990s, Engler also made under-the-radar changes to energy efficiency standards that were difficult to combat. After receiving complaints from electric companies, the Michigan Public Service Commission under Engler eliminated a requirement for investor-owned utilities to invest $80 million annually on energy efficiency programs. Utilities and homebuilding companies also persuaded the state legislature to repeal a decision to adhere to the national Model Energy Code for energy efficient design of new buildings, setting up Michigan residents to pay more for heating and cooling for decades to come.

These energy policies did more than just increase Michigan residents’ energy bills: they also increased the state’s dependence on fossil fuels. More than half a decade after Engler left office, Michigan was importing 100% of its coal and uranium, as well as 96% of its oil and 75% of its natural gas. These imported fuels sent $20 billion out of Michigan’s economy annually, in addition to spewing unnecessary and harmful carbon emissions and pollution into our air. Engler resisted efforts to gather environmental data that might affect his policy gifts to corporate polluters, repeatedly spurning environmental efforts led by other states in the Great Lakes Basin and frequently declining funds from federal agencies to study climate issues.

Defending Against Long-Term Damage, Making Long-Term Progress

John Engler’s tenure as Governor was marked by other exercises of power that consistently prioritized big business’s wishes, with careless disregard for the health of the Michigan public. Many of the era’s environmental policies exacted an especially high cost on children, on low-income communities, and on people of color.

The Ecology Center found that 108 of the Engler administration’s newly weakened pollution standards completely neglected to consider children’s health and development in their risk calculations. The emergency management the Engler administration forced on the city of Flint--the first of four emergency managers the city was to endure over 30 years--set the stage for citizen disenfranchisement and lack of democratic accountability that culminated in the water crisis that continues to poison the city. Other major deregulation initiatives led to weakened fish consumption advisories and wetland protections that continue to threaten the resources of the state and the health of its residents.

The Ecology Center worked hard to defend against the Engler’s administration’s comprehensive dismantling of state environmental standards and structures. We joined and led lawsuits to fight Engler’s reversals, engaged membership to unite in public opposition to the administration’s deregulation efforts, and disseminated original expert research findings as a nonprofit watchdog. These efforts are highlighted in other stories we’ll share, but here we want to be crystal clear about the big picture: it was an uphill battle for the environmental community to combat Engler’s policies and their successful implementation.

Given the continuing legacy of the Engler years, the Ecology Center’s current strategies include shoring up protections and policies that were more progressive 30 years ago, while imagining new infrastructure and policies we need to meet challenges that are better understood and even more urgent today, especially the climate crisis. We make progress through research, policy advocacy, education, and grassroots citizen mobilization--and we know that citizen mobilization, especially voting, is the most powerful tool we have.

The results of elections set the stage for whether movements are able to substantially advance progress, or whether they’re compelled to direct their energy toward defense and resistance. Once John Engler was elected Governor, there was only so much environmentalists could do. He used his power as an elected official to side with the rich and powerful few, at great cost to everyone else, and we’re still cleaning up the damage done.

Research for these stories provided by the Environmental Justice HistoryLab at the University of Michigan. For more details, check out our history archive.