It started with a 17-hour drive across the Midwest in a car filled with $20,000 worth of air quality monitoring equipment.

The rest of the cohort followed by airplane a few days later.

The league of environmental justice champions from southeast Michigan included Donele Wilkins of Green Door Initiative, Theresa Landrum from the Original United Citizens of Southwest Detroit (48217), Roshan Krishnan from Michigan Environmental Justice Coalition, Raquel Garcia from Southwest Detroit Environmental Vision, and Kathryn Savoie and Jeff Gearhart from the Ecology Center.

The Detroit group was headed to the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota to meet with indigenous activists from the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nations, known as the Three Affiliated Tribes. Their activist counterparts in North Dakota were from the Dakota Resource Council and the Fort Berthold Protectors of Water and Earth Rights (POWER).

For years, both groups of advocates had been fighting the same offender: the petrochemical industry. And though they lived thousands of miles apart and on separate ends of the supply chain – extraction in North Dakota and refining in Michigan – both parties suffered from the same ailment: toxic air pollution.

It made sense that the two groups meet to swap notes and support each other.

The goals of the meet-up were two-fold.

First, collect data. Tribal members knew fracking operations were impacting their air quality and their health. But without air monitors on the reservation, they had no evidence. An air monitor network, the first on the Fort Berthold Reservation, would provide much-needed data to support their requests for stronger regulation.

Second, build power. The two groups planned to share knowledge and create community among themselves. With an adversary as rich as the oil and gas industry, the only effective tactic to counterbalance their wealth of resources is to build people’s power to push back.

The trip helped to develop relations between our two communities. We have more in common than not,” said Raquel Garcia, executive director of Southwest Detroit Environmental Vision. “We were able to dive in and learn about each other's communities and become invested in each other's projects and visions.

But how did folks from Detroit and tribal members in rural North Dakota end up with air pollution from the same industry, even, at times, the same company? The Detroiters were about to learn the reason.

The Ever-Shrinking Sovereign Territory of Fort Berthold

The first stop on the reservation for the Detroit leaders was the Three Affiliated Tribes Museum in New Town, North Dakota, where they learned the history of the tribe and the land.

Upon entering the museum, there hangs a photo of an indigenous man, head bowed, weeping as he bends to sign a document. The document he is signing will give away the tribe’s land rights to the United States for little in return. And while the photo is from the 1940s, the sentiment captured could be from any time in the last 200 years.

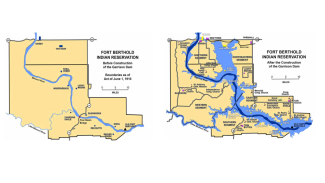

When first recognized by the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1851, the Fort Berthold reservation encompassed 12 million acres. Today, the reservation comprises slightly less than a million. Repeated land confiscation by the United States government and the impacts of the Dawes Act, which broke up communally-owned land into individually-owned parcels, resulted in the increasingly shrinking territory of the Three Affiliated Tribes.

Nonetheless, before the 1950s, the reservation was self-sustaining, with tribal members raising livestock and farming the land around the banks of the Missouri River, which splits the reservation on a northwest-to-southeast diagonal. Sadly, following the Flood Control Act of 1944, the United States Army Corps of Engineers installed the Garrison Dam on the Missouri River, flooding out more than 150,000 acres of reservation land. The effects of the dam on the tribal nation were devastating – 325 families, representing 80% of the tribal membership, were forced to relocate to higher ground when the rising water submerged their homes, towns, churches, and graveyards. The tribe lost nearly all of its agricultural land.

When the oil and gas companies came knocking on the tribe’s door in the early 2000s, it’s likely the residents were not surprised that the white people had come to take from them again.

That the reservation was sitting atop rich oil and gas reserves had been well established. But excavating it had been cost-prohibitive until the industry perfected the technique of hydraulic fracturing, known colloquially as fracking.

The fracking boom in North Dakota took off in 2008 and the state quickly became one of the top oil-producing states in America.

When land is fracked, after drilling deep into the Bakken shale bed, a high-pressure mixture of water, sand, and chemicals is shot horizontally into the bedrock, creating fractures. These fractures are held open by sand in the fracking fluid, from which escapes that treasured substance: oil and gas.

But that’s not all – methane, a highly potent greenhouse gas, is also pushed out during fracking, sometimes so much so that the gas must be flared, or lit, to burn off the excess gas. The flares on the reservation and west North Dakota shine so brightly they can be seen from space.

Along with methane, fracking operations release toxic petroleum hydrocarbons like benzene, toluene, and xylene, and increase ground-level ozone. The industry also brought heavy-duty truck traffic clamoring through the area, kicking up dust, increasing truck-related traffic fatalities, and further polluting the air with diesel emissions.

Our environmental justice team had come to help investigate these air pollutants.

“We hold all of Mother Earth sacred, including the air.”

After learning the history of the land, the group met with a longtime activist and recently elected state House of Representatives member, Lisa Finley-DeVille. Lisa has been working on air quality and environmental justice on the reservation for many years.

The people of my tribe, The Three Affiliated Tribes, have lived on and cared for our land for millennia. We hold all of Mother Earth sacred, including the air,” said Lisa, as reported by Buffalo’s Fire in 2021. “Since the start of the Bakken oil boom, the oil and gas industry has polluted our air and harmed our health by flaring and venting methane from wells and pipelines.

Lisa and her husband gave their visitors a tour of the reservation, highlighting the toxic legacy of the oil and gas industry. They brought them up to date on how the community had been working to combat the negative impacts of fracking and flaring around the reservation.

Together, the group installed the last of the seven air monitors on the rolling grasslands, with grazing horses, jutting buttes, and robotic well pumps dotting the landscape behind them. An air sampling device, which pulls air into a canister when toxic compounds are detected, was also installed to provide definitive evidence of pollutants present.

The data from the monitors will be displayed on an online dashboard to allow people to access real-time information about the air they breathe. After six months, the compiled data will be shared with the community and elected officials so they can take informed action and work on policy solutions. Colorado State University will analyze the samples collected for toxic air pollutants like methane and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) like benzene, toluene, and ethane.

“We need to move away from fossil fuels”

The environmental justice leaders from Detroit were well-versed in community-based air monitoring. The group has worked together for the past two years to install a neighborhood-level monitoring network in their city. Most of the group had worked on environmental justice in their communities for decades.

Detroit and nearby municipalities suffer more from poor air quality and higher asthma rates than any other Michigan community. The University of Michigan estimates over 700 premature deaths occur annually in Detroit from exposure to pollution.

One of the decades-long advocates is Theresa Landrum, who lives in southwest Detroit. Her neighbors, mostly Black homeowners, have passed their houses down through multiple generations. Across the street from her neighborhood’s community center is an oil refinery, one of the dozens of industrial sites nearby. Her zip code, 48217, is number one in air pollution in Michigan. According to the EPA, a disproportionate amount of people have asthma and cancer in her neighborhood, likely due to sulfur dioxide emitted from the plant.

For years, she has raised awareness in her community about the dangers of emissions, brought elected officials and media on toxic tours of the industrial sites, and supported policy and planning efforts to end air pollution.

Traveling to North Dakota with the Ecology Center to learn about fracking, the area concerns, the history of the area, and forming allies across the country deepened my understanding and urgency of why we need to move away from fossil fuels even more,” said Theresa.

Like their indigenous allies, air pollution was just one of the problems inflicted on their Detroit communities. Racist planning policies put industrial and manufacturing facilities, an incinerator, and highways in their backyards, impacting their health and local economies and displacing hundreds of families.

Building Community Power at the Parshall Powwow

After three days of learning and information sharing, the group celebrated by attending a local powwow in nearby Parshall, North Dakota. They enjoyed traditional Native American foods like fry bread. The sound of drums echoed throughout while folks of all ages, from toddlers to elders, were called up to dance. Those present celebrated their community, culture, and shared resilience in carrying it forward.

In October, the North Dakota partners returned the visit and came to Detroit to reconnect with the Detroit environmental justice activists and learn about the impact of the oil and gas industry in the city.

Together, the groups will work to build power and share advocacy and policy solutions. And hopefully, one day, the air will be clearer in both communities.

To view the air quality monitoring dashboard on the Fort Berthold Reservation, visit the Just Air portal.