One of 50 stories, from 50 years of action

"What is at issue are the needless negative impacts that unwise development has and can have upon our sense of place, upon the quality of our lives, and upon our economic and social well-being.” Christopher Graham, Ecology Reports, April 1994

Why was suburban sprawl such an important issue in the 1990s?

Since its founding, the Ecology Center has been at the forefront of efforts to stop suburban sprawl. Some early campaigns, like blocking the “Super Sewer” wastewater treatment plant in the 1970s, resulted in victories; other efforts, like organizing against the Briarwood shopping center development, were not successful.

Like many environmental issues, urban sprawl is not a single-stakeholder issue. Washtenaw County residents worried about changes to their lifestyle if the region became suburbanized. Environmentalists feared the loss of natural resources and farmland. Social justice advocates expressed concern about development contributing to ongoing “white flight” from urban areas and drawing infrastructure dollars away from cities with large populations of color.

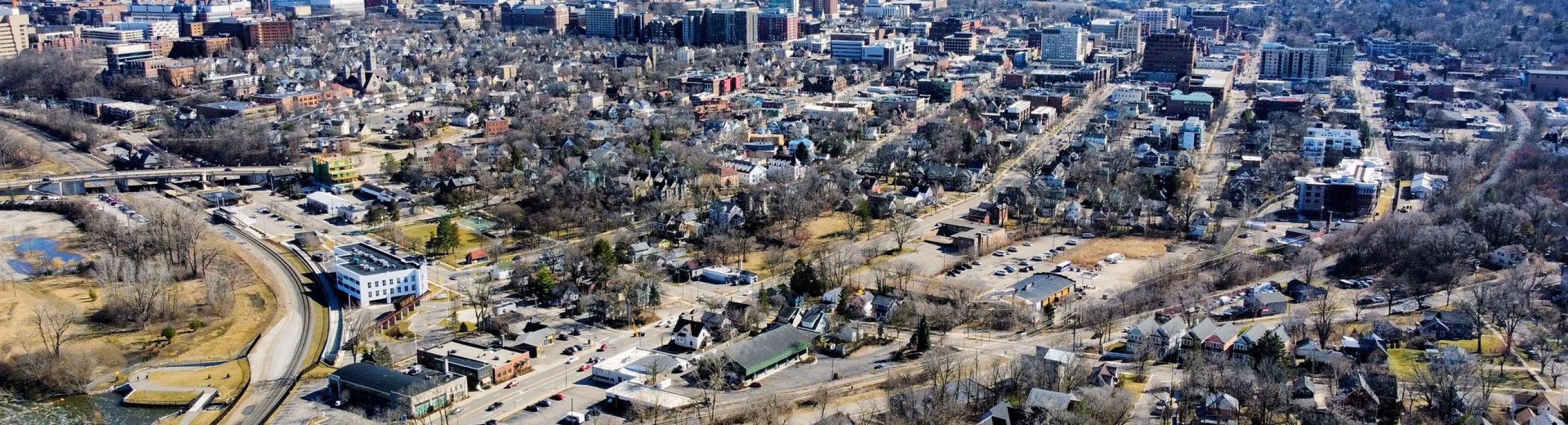

In the 1980s and 1990s, urban sprawl – “development that lacks a functional relationship to land, is auto dependent, and that requires excessive road construction” – transformed many Washtenaw County farms and open spaces into subdivisions. Between 1969 and 1987, Washtenaw County lost over 56,000 acres of farmland and new residential areas cut through ecologically significant locations and watersheds. The trend continued throughout the next decade. Planning professionals predicted that farms would disappear from Washtenaw County and most of southeast Michigan by 2020.

The primary factor enabling the loss of open space and farmland was the total control over development afforded to villages, cities, and townships under Michigan law (the State of Michigan has more local planning jurisdictions than any other state). The multiplicity of land use authorities meant communities competed with each other to attract development and grow their tax base, consequently regional planning was virtually impossible.

What did the Ecology Center propose for solving the problem, and what were the politics of implementing?

Michigan’s land use laws meant that the only viable way to contain sprawl on a large-scale and in an enduring way was at the county level. In 1993, the Ecology Center helped form an unlikely coalition of farm organizations, environmentalists, and social justice organizations to campaign for anti-sprawl solutions. Four years later, a County Task Force recommended a 0.4 mill property tax to fund programs preserving agricultural land and natural areas; providing planning assistance to township governments; and undertaking brownfield redevelopments. Central to the recommendation was a Purchase of Development Rights (PDR) program. PDR agreements offered landholders a cash payment in exchange for prohibiting subsequent development of the property. The program offered an alternative for landowners to benefit from the equity in their property, which was the “retirement plan” for many farmers.

The PDR millage, put to Washtenaw County voters as Proposal 1, would have made Washtenaw the first county in Michigan to have a tax-supported PDR program. Supporters and opponents alike anticipated approval might pave the way for a statewide PDR proposal, consequently the initiative generated unprecedented attention throughout Michigan. Supporters of Proposal 1, led by the Democratic former State Senator and environmental leader Lana Pollack and the Republican former Commerce Secretary Keith Molin, waged a massive campaign with participation from the environmental, agricultural, faith, and business communities, and which won the support of virtually all of the county’s political leadership. The Ecology Center and the local chapter of the Sierra Club led the grassroots portion of the campaign, marshalling more than 600 volunteers in what was then an unprecedented effort to knock on doors and call prospective voters to “Save our land, save our future.”

The all-hands campaign was essential, because two of the state’s most powerful political forces – the home builders association and the realtors lobby – were dead-set against the plan. Their local affiliates recruited financial support from developers across the state, and spent more money to defeat the proposal – largely through TV advertising – than any campaign had ever before spent in county politics. Aware of polling data that found the proposal extremely popular among all groups of county voters, the home builders and realtors kept a low profile while spending more than $250,000 to persuade county residents that the farmland preservation program would actually be bad for farmers. Their ad campaign overwhelmed grassroots efforts in favor of the proposal, and voters eventually defeated the measure at the ballot box by 57.5 percent to 42.5 percent.

Undeterred, the Ecology Center kept up the fight, and developed new plans to pass portions of Proposal 1 in stages. The first measure was a proposal to create a countywide natural areas program, a less controversial piece of the 1998 package, through a millage request on the 2000 election ballot. The Ecology Center and Sierra Club reassembled most of the 1998 anti-sprawl coalition, persuaded the Board of Realtors to switch sides, and managed to keep the home builders neutral on the question. After another huge grassroots public education campaign, the natural areas proposal was approved with over 64% of the vote.

What's been the legacy of the successful land preservation programs?

In spite of the bitter conflict that birthed the initiative, the county’s Natural Areas program has retained its popularity through twenty years of operations and one millage renewal in 2010. The program has permanently protected over 3,400 acres of land with ecological, recreational, and educational benefits. These spaces provide residents with opportunities for learning and leisure, are located in every corner of the county, and are connected to Washtenaw County’s Border-to-Border Trail, the park systems of Ann Arbor, Ypsilanti, and recreational areas in other communities – many of which were also developed in part through the work of the Ecology Center.

The success of the Natural Areas campaign in 2000 was just the first big step forward in an ongoing fight to contain sprawl in Washtenaw County. There remained work left undone to preserve farmland and build stronger cities. The Ecology Center and its collaborators again took up the fight against developers during the Greenbelt Campaign of 2003 and for related campaigns soon after. Stay tuned for part 2 of “The Fight Against Developers,” scheduled for release later this year.

Research for this article provided by the Environmental Justice HistoryLab at the University of Michigan. For more, see history archive.

Created in partnership with the Environmental Justice HistoryLab at the University of Michigan. More Information.