By Tracey Easthope and Elizabeth Harlow

Fifty-one years ago today, Elizabeth Grant Kingwill and seven other advocates formally founded the Ecology Center, as the organizers of America’s first and largest Earth Day events planned to keep the spirit of the new grassroots environmental movement alive. Celebrating our anniversary today, we marvel at the optimism and strategic acumen of the founders, and at the grit, creativity, and courage of the organization over the decades. Nearly one third of nonprofit organizations don’t even make it ten years, but thanks to your support, we are stable and strong!

We were thinking about what it takes for a nonprofit, and for a movement, to thrive when we were recently asked to honor our late colleague Mary Beth Doyle as part of the celebration of Women’s History Month. Mary Beth was a fierce, brilliant, and strategic environmental advocate, but we remember her most for her indomitable spirit, her insistence on having fun, her energy for the attention-getting gesture, her determination, moxie, and grit.

Mary Beth helped elevate the profile of some of our most important campaigns, and in her honor, we delight in them again on this anniversary. Here are some of the more colorful highlights of her advocacy.

A Sense of Fun: Elvis Impersonators Headline “Return to Sender Trash Bash Tour”

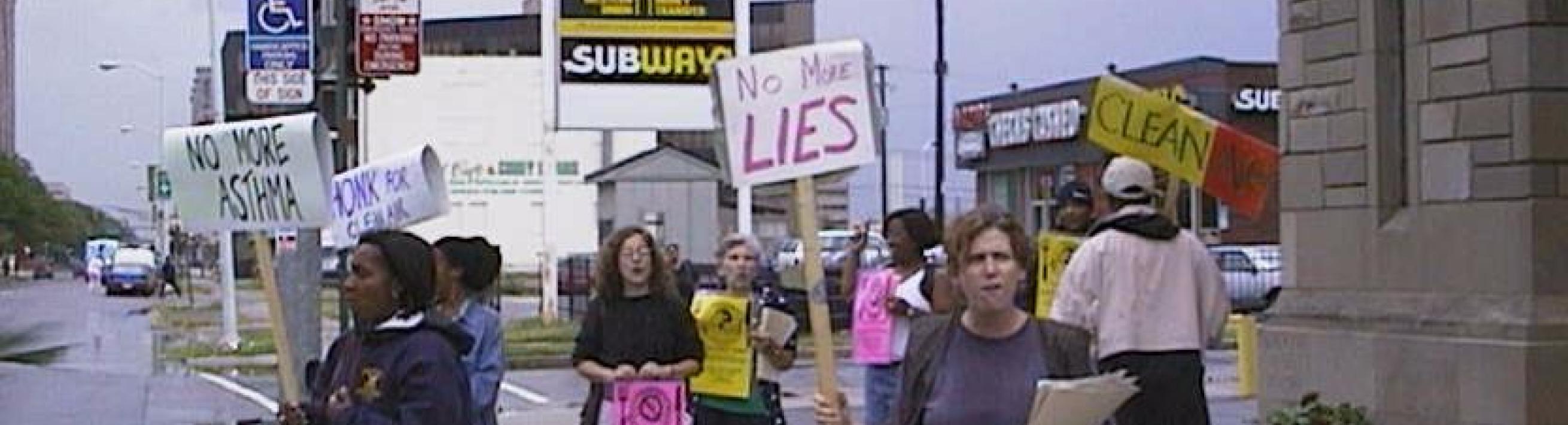

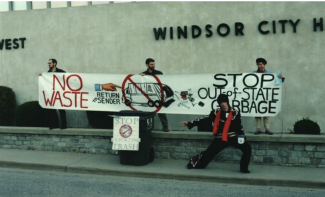

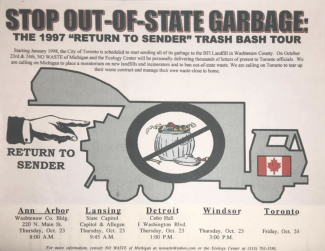

In late October 1997, Michigan and Ontario radio stations played an unfamiliar version of a familiar Elvis Presley classic. “Send us bacon and hockey,/Beer and curling, too,/But if you send us your garbage,/ We’ll send it right back to you,” crooned an environmentalist “Elvis” in Mary Beth’s rewriting of “Return to Sender.” The state of Michigan had recently allowed a glut of new landfills to open, and the city of Toronto was on the cusp of dumping the entirety of its waste in Northville, MI. The Ecology Center helped lead a coalition called the Network of Waste Activists Stopping Trash Exports, or NO-WASTE, to resist massive trash imports like Toronto’s.

Listen to the NO-WASTE version of “Return to Sender”

Any new hit deserves a tour, so Mary Beth recruited a series of Elvis impersonators to join NO-WASTE activists to serenade legislators and decision makers on both sides of the border. They toured from Ann Arbor to Lansing to Windsor to Toronto on a recycling truck stuffed full with letters from Michigan citizens to future Toronto Mayor Mel Lastman, and to his leading challenger, demanding an end to garbage being shipped to Michigan.

Mary Beth’s creative approach garnered lots of attention for the international garbage issue. The song even eased the recycling truck’s border crossing, because Customs’ officials had heard it on the radio and waved the truck through. The campaign eventually led Toronto to institute a very strong recycling and organics program. It also spurred federal hearings about waste imports in the U.S., and launched a debate about Michigan landfill policy in the early 2000s. Michigan is still a dumping ground for trash from all over the Midwest, but less so from Canada. In 2016, the State of Michigan invested significantly in rebuilding its state recycling program, and in 2018, the Michigan Recycling Coalition succeeded in winning an $18 million budget allocation for new recycling initiatives, which is being disbursed to local communities now.

Moxie and Determination: Housewives Rise Up!

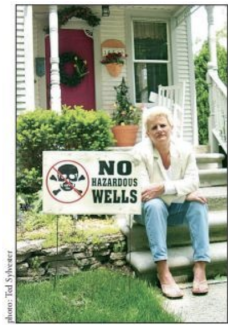

For more than 15 years starting in 1990, the citizens of Romulus, MI fought against a commercial deep injection well proposed for their already environmentally burdened community (as of 1997, the city had one toxic waste facility for every 140 residents). The well, in a majority minority residential neighborhood, was designed to pump 100 million gallons of liquid waste per year into the ground, most of it hazardous. It was also the first commercial injection facility in the entire EPA region. The spirited, persistent, and creative opposition to this groundwater pollution threat was led, in part, by some courageous, heroic, and strategic women, and supported by a majority of the community.

At one point, Douglas Wicklund, the president of the company that owned the well, Environmental Disposal Systems, tried to dismiss the opposition as a bunch of “housewives.” Never one to let a sexist stereotype go unchallenged, Mary Beth turned the tables by organizing a group of advocates to protest at Wicklund’s home in curlers, robes, and slippers. The protest was widely covered and set the terms of the struggle starkly.

Claiming no local jurisdiction had any authority over the well, EDS built it and a second one over the objections of nearly everyone, completing construction in 1993. However, the site remained embroiled in litigation for the next decade.

In 2004, EDS looked poised to finally win its war against the persistent and long-successful Romulus community, but in a stunning development, the DEQ decided not to grant the final permit required to operate the 11-year old unopened hazardous waste facility. Ultimately, the well did open the next year, but only briefly. As advocates had predicted, it contaminated the injection area, and had numerous violations. The community continued speaking up, and the well shuttered again in 2006. Today, a recent title change has led to community meetings with citizens again demanding transparency and accountability, and fighting any new activity.

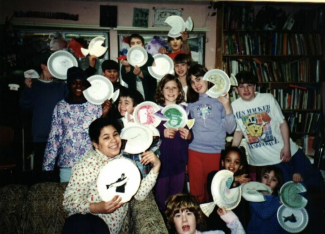

A Crafty Attention-Getting Gesture: Fish Plates

At the Ecology Center, Mary Beth and Tracey Easthope brainstormed ways to put pressure on the Engler Administration to adopt the uniform advisories to better protect subsistence anglers who relied on fish for their major protein source. They knew they needed something to draw attention to the issue, and to educate the broader community about the dangers of eating certain fish, so they decided to enlist people, particularly children, in decorating paper plates with images of the fish they might have for dinner and then sent them to lawmakers. The campaign caught on, and some schools had students decorate plates while learning about fish and fish advisories. Paper plate decorating was featured at Earth Day festivals, and other sustainability events.

Enough paper plates made their way to Lansing that advisors surrounding the governor took notice. After the outpouring of community feedback and coordinated pressure from the Ecology Center-led Environmental Health Coalition and allies including the Michigan Environmental Council, John Engler finally reversed his position. Michigan adopted the more protective fish consumption limits for women of childbearing years and children and required posted warnings at fishing sites.

Mary Beth’s legacy extended beyond joyful protests. She helped organize one of the country's first major conferences on endocrine disrupting chemicals, sat on NGO Boards at the state and national level, secured early wins in the fight to make children’s toys less toxic, helped communities shutter medical and municipal incinerators, was a major player in national and international environmental health and justice coalitions, worked to advance alternative treatment technologies for waste, and much more.

Mary Beth was influential locally in Washtenaw County, as well, coordinating the grassroots portion of the successful People for Parks campaign to pass a citizen-initiated millage proposal for parkland acquisition, later expanded into the Greenbelt Program. She helped pass a municipal ban on mercury thermometers in Ann Arbor – at the time, the third in the country – and then helped with the successful statewide ban.

Mary Beth Doyle’s legacy lives on in the world, and in our work. She reminds us of the power that each of us holds when we bring our unique gifts and skills, our energy and determination, to the work of making the world better, brighter, more hopeful, more equitable, and more fun.

To celebrate the Ecology Center’s five decades of moxie, determination, and fun, please look out for invitations, coming soon, to a terrific virtual event this October, and an in-person celebration next spring.

For more on her legacy, listen to Ecology Center Deputy Director Rebecca Meuninck’s recent interview about Mary Beth on WEMU or dig into our 2005 newsletter paying tribute to her life and work.

The Ecology Center’s Rise Up anniversary story series is made possible in part by the Rackham Program in Public Scholarship and the University of Michigan Office of Research, and research for these stories has been conducted in partnership with Environmental Justice HistoryLab at the University of Michigan. For more details on all three campaigns featured in this story, check out our history archive.