by Elizabeth Harlow

Ash and Cash

When the Detroit trash incinerator went online in 1989, it was the largest trash-to-energy incinerator in the world. At a cost of $438 million, it was the most expensive single project the City of Detroit had ever undertaken. Its operation turned out to be a costly disaster for Detroiters until 2019: the neighboring community suffered from high levels of asthma-inducing air pollution and endured a stench that made backyards unusable, while taxpayers lost millions.

Residents fought to keep the plant from opening, and then to shut it down, for thirty years.

As a health hazard and noxious neighbor, the incinerator drew protest from citizens, environmental coalitions, and Canadian leaders across the river since planning began in the mid 1970s. Mayor Coleman Young and City officials nevertheless forged ahead to build it, betting that the costly incinerator would ultimately save the city money with a long term waste management plan and state-of-the-art technology.

The gamble failed spectacularly. In debt and losing roughly $2M each year on the facility, the City opted to sell the incinerator in 1991 to reduce a budget deficit, just two years after the plant opened. They didn’t sell the construction bonds, however, and Detroit citizens ultimately paid $1.2 billion in incinerator debt, which dogged Detroit into bankruptcy in 2013.

A Noxious Neighbor

The incinerator failed to meet emission standards even when it was brand new. A Detroit Free Press commentator noted in 1989 that “[e]ven the EPA has admitted that it botched things by originally granting approval” in 1984. The plant experienced its first shutdown over violations in 1990, just a week after the city’s first permanent recycling center opened. Several hundred protestors celebrated and staged a mock funeral with cardboard coffins outside the facility.

The incinerator made some mandated upgrades to come into legal compliance and then reopened. The battle went on like this for decades. But the incinerator also started accepting trash from all over the region, most notably from the wealthier surrounding suburbs. The Ecology Center worked on and off with community groups throughout these years to challenge the incinerator.

In the mid-2000s, the Ecology Center joined with environmental justice organizations and community groups to renew the fight against the Detroit incinerator, and to promote zero waste in Detroit. The Zero Waste Detroit (ZWD) coalition promoted a positive vision of a zero waste future and fiercely organized to close the facility, securing temporary closures of the incinerator as it continued to violate clean air laws while burning over 850,000 tons of trash each year, mostly from more affluent communities outside of Detroit.

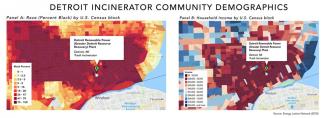

The incinerator spewed gases like sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide, and heavy metals such as lead, mercury, and cadmium. It spewed them into residential neighborhoods, including 13 schools and 22,000 people living within a 1.5 mile radius of the smokestack in 2018. People living in the vicinity of the incinerator faced a higher rate of asthma than anywhere else in the state. In a textbook case of environmental racism in America’s largest majority minority city, the closest neighborhoods were and are mostly black and brown and poor, comprised by 76 percent people of color and 71 percent low income families in 2018.

Breathe Free Detroit

In 2015, two of Zero Waste Detroit’s member organizations--the Ecology Center and East Michigan Environmental Action Council (EMEAC)--again reinvigorated efforts to shut down the incinerator. These efforts coalesced formally into the Breathe Free Detroit campaign in 2017 when community members leading the efforts, including Ecology Center’s Kathryn Savoie and Melissa Cooper Sargent, saw an opportunity: the state had announced a public hearing in response to residents' many odor complaints and other documented violations.

As its first official event, Breathe Free Detroit hosted a community forum to educate community members on how to give effective testimony at a public hearing, resulting in a powerful showing at the hearing. An estimated 150 people attended with about 50 providing influential personal testimony.

For the next two years, the Breathe Free Detroit campaign continued to organize residents in the surrounding neighborhoods to call for the facility’s closure, amplifying the volume of complaints and concerns that had been voiced and dismissed for so long.

Residents filed odor complaints with the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, attended further public hearings, and staged demonstrations to demand relief. In 2018, the campaign published a comprehensive analysis of the incinerator’s operation conducted by the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center, including documentation of over 750 air permit violations in the span of just three years.

Campaign participants rallied for a press release to deliver the report personally to Mayor Mike Duggan’s office, alongside a petition signed by almost 15,000 people. The action generated increased incinerator coverage in the Detroit Free Press, Detroit News, and other local media, breaking into national news as well.

The Ecology Center and Environment Michigan dealt the final blow to the beleaguered incinerator in February 2019 by filing a notice of intent to sue Detroit Renewable Power (DRP), the owner of the incinerator, for its hundreds of air permit violations. Anticipating a negative judgment that would force major capital upgrades to the facility, DRP closed the incinerator a week before the lawsuit would have been filed, with acknowledgment that they couldn’t be a “good neighbor” and a profitable business entity at the same time.

Detroit After Incineration

Ecology Center and Environment Michigan still have a citizen suit pending against DRP and hope a negotiated settlement may bring some restitution to residents forced to endure the incinerator’s egregious and illegal pollution. While legal negotiations continue, the Breathe Free Detroit campaign continues fighting for the neighborhoods around the incinerator, tackling gentrification and other issues.

With Detroit’s longtime worst polluter finally gone, the Ecology Center’s focus has turned to making Detroit a zero waste mecca, while also tackling other air quality threats in the city. Recently, we’ve deployed air monitors to give residents real-time information on air problems.

Created in partnership with the Environmental Justice HistoryLab at the University of Michigan. More Information.