This interview is the first in a series highlighting leaders working on environmental health & justice.

Darren Riley, CEO and co-founder of air quality justice tech startup, JustAir, envisions a world where the breeze passing through city neighborhoods is not clogged with the burnt and rotten smells of diesel emanating from highway traffic, where children tossing a ball in their yard no longer find themselves coughing against the putrid stench of exhaust from factories. This is why he founded JustAir: to connect community members with street-level, minute-to-minute information about hyperlocal air quality via an easy-to-use app, so they can plan to stay away from streets holding onto harmful air pollution in any given hour of any given day.

Air pollutants from industrial manufacturing and trucking traffic – most concentrated in working-class neighborhoods – harm human respiratory, cognitive, and mental health and intensify the effects of climate change. Responding to this urgent need, the Ecology Center and eight community and non-profit organizations have come together in collaboration to plan for clean air in Wayne County.

JustAir is a member of this collaborative. Founded in Grand Rapids and now headquartered in Detroit, the rapidly expanding environmental tech organization is growing to encompass cities across the country, carrying with it an ethic of community-listening that has ensured they are responding to the unique needs of each place. We had the opportunity to talk with CEO and co-founder Darren Riley about his organization and the deep-rooted need for air quality justice in and beyond Detroit. Darren also serves as co-chair of the data monitoring working group for a collaboration of community partners.

(This interview has been edited for clarity and length.)

Tell us about JustAir – what inspired you to create this organization?

JustAir’s mission is to ensure everyone has equal access to clean air. I got into this space through a combination of both my personal and professional experience. I’ve always done work in tech. As a graduate of Carnegie Mellon University, I did cybersecurity work and moved to Detroit to focus on the entrepreneurial ecosystem, particularly around social impact entrepreneurship. I was fascinated by how we create a business landscape that does right through the work that they do.

Then I developed asthma five years ago. I currently reside in southwest Detroit – a little too close for comfort from the Ambassador Bridge close by. [The bridge, which connects Detroit with Windsor, Canada, is the busiest international crossing in North America and a major source of diesel exhaust pollutants from its heavy traffic.] I’m a product of my environment and some of the illnesses definitely got exacerbated by the place where I live.

Around 2020, with the murder of George Floyd and COVID, everyone had their heads up, looking at some of the inequities and injustice.

I wanted to use my experiences to make a difference, particularly around the community that I come from. Our goal is pretty simple: 1) create awareness and access to air quality data at a neighborhood level, but also 2) enact change. So, use our infrastructure to not only inform change, but also to measure impact. Solutions and awareness is what we’re all about for environmental justice.

We’re not trying to jump in and say, “Hey, look what we got: some shiny toys that can maybe help out.” We want to learn from community members, neighborhood associations, community workshops, churches and places of worship, what’s going on in the community.

Can you share some of JustAir’s accomplishments that you’re most proud of?

When I first started JustAir, I was thinking cities wouldn’t want to support something like this, but I’ve been proven wrong. I’m seeing a lot of cities being proactive around their environment and protecting the health of their community. I’m excited to see that trend moving in the right direction.

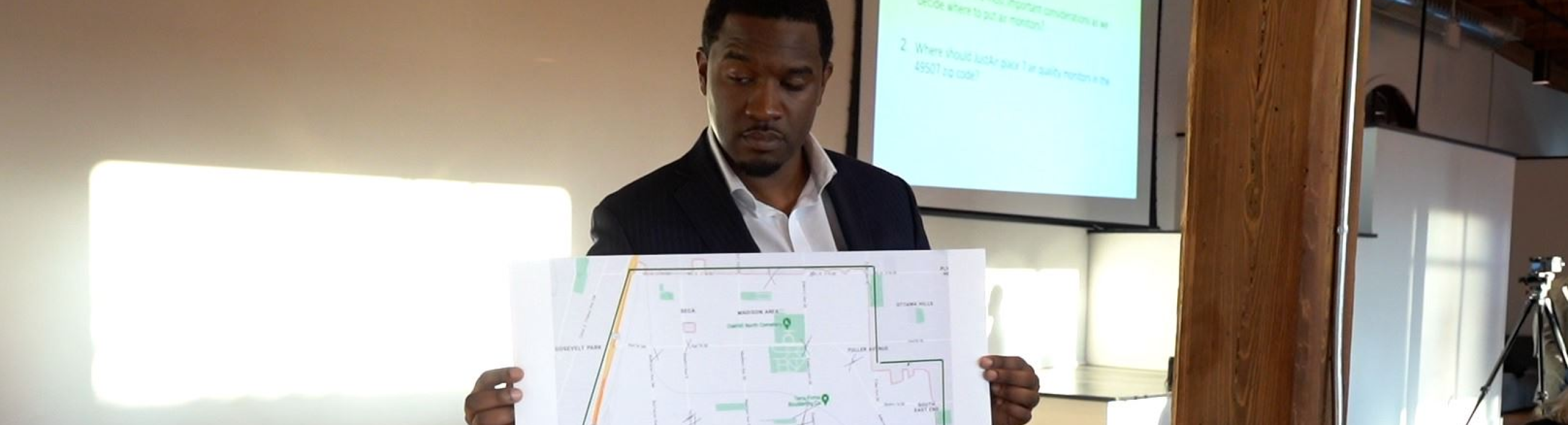

One thing I’m really proud of is the deep community work that we’ve done. For example, in Grand Rapids last week, we had a community air quality workshop, where we had residents learn about the project that we’re doing in a zip code with one of the highest environmental justice scores in the state of Michigan, a predominately Black and Brown community. We wanted to make sure that they had control over where the monitors go up. We’re deploying seven monitors within that community. Community members got to learn about air quality, learn about the project, and, most of all, got to learn what this monitoring device does and where it goes.

Community members were saying, “Hey, this asphalt plant is something I’m concerned about.” “Hey, my kids are going to school here. I would love to learn what they’re breathing, if they’re spending the majority of their time and their week at that facility.” “Oh, this highway rips through our community. Let’s put a couple of monitors up there.” This is some of the feedback that we’re getting.

When you’re doing this work, it’s important not to just come and say, “Hey, we’re going to just throw monitors up, and off you go.” It’s important to work with the community and get people up to speed and understanding what it is that they’re reading and how to make decisions based on the data we’re providing.

Why is neighborhood-level air monitoring so important?

We need to pay attention to the water we drink, the food we eat, and the air we breathe.

We look at the expiration date on our food, we are very strict around the quality of our drinking water. And we should have the same rigor around the air that we breathe.

Because of the 1970 Clean Air Act, many major urban cities have maybe one, maybe two, or three reference monitors. But where you are in relation to that reference monitor will have a large impact on the quality of your data and how relevant it is to you. If I live three or five miles from a monitor, that has a different flavor than if I’m a couple blocks away. The goal with neighborhood-level monitoring is pretty straightforward: the more granular we can get, the more relevant data can be to every resident to make sure they have access to clean air.

What causes air quality differences based on neighborhood?

There are a lot of different potential causes. I live next to a highway with high trucking traffic. Studies say you shouldn’t live 1,500 feet from heavy-density trucking traffic – where I live is less than 1,000 feet from the Ambassador Bridge. That can result in emissions of black carbon (soot) and CO2. Some of those emissions, especially on hot days where ground ozone is elevated, can exacerbate long-term diseases like asthma or COPD, or even accelerate cognitive issues, from childhood development to Alzheimer’s, and cancers as well.

I’ll look at it in twofold: one, what are sources of air pollution? It could be industrial activity, like trucking traffic. I also look at what mitigating factors are not present. For example, tree canopy. Trees cool our communities down a bit. If lowering the heat can help limit pollutants catalyzing and affecting humans and also absorb a lot of the chemicals, this is what’s good. We try to avoid the concrete jungle.

There are preventative things that we can do – tree canopying, electrification, and things like that. And then there are all the sources that are contributing.

We need to add more of the good stuff and remove some of the bad stuff that can impact a neighborhood disproportionately, depending on where they’re located.

What neighborhoods are most impacted by air pollution?

Often we see communities that are right on the edge of an industrial zone, fenceline communities, having to deal with higher rates of asthma and higher rates of emergency visits related to pulmonary diseases.

We even know that certain communities’ home values are affected: because of the soot that may be on the exterior of their house or because their house shakes a bit or has infrastructure issues. We’ve heard from community members [in Detroit] that at certain times of the day, trucking traffic shakes their homes’ foundation, and that can distress them. Sleep may be a little bit more difficult, which can also add to the stress. There are so many different factors, not just from a health perspective, but mental health, too.

Your quality of life and your ability to enjoy this life shouldn’t be determined by your skin color or where you were born. Pretty simple.

From an economic perspective, if you have asthma or you have issues that you are more vulnerable to triggers, that can affect you and your workplace. You’re hurting people’s pockets.

In education, there are studies that have shown that for kids in higher polluted areas, and even service workers, on high-pollution days, near-term memory is limited. That can affect your test scores, your attention span, and your day-to-day work. When you look at disparities, it threads the needle through a lot of different major topics that are important for life: economics, your health, and also your community.

What might people find surprising about air quality justice?

They might not realize that air quality is something that we can change, that we can improve.

People might think, “Oh, air quality is the air quality. I have to either move or tolerate what I’ve been born into.” The most important thing in this work is to realize that we do have an active voice and agency over what we like to accept as citizens or residents, or taxpayers. It’s essential to start with that.

Another cool nerdy thing is how one of the biggest contributors to water pollution is air pollution. That makes sense; things settle in the water. When we focus our attention on the Great Lakes and our other sources of drinking water, we have to be very mindful of the air surrounding that.

Now, a lot more studies are coming out about the effects of air pollution on our brains. We have always known about asthma and cardiovascular issues. Not to downplay how critical those are, but we should also know that memory and early childhood development are extremely affected by air pollution. Our children are our future, and I want to make sure they have a safe space to learn and grow and thrive and be the best that they can be. That one surprised me, how air pollution can directly affect the brain. And more so, it drives in how important it is for us to continue doing good work and for our communities to thrive.

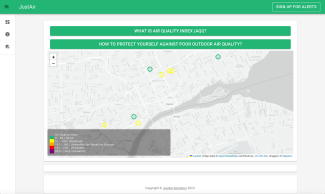

You just launched a new dashboard with neighborhood-level air monitor data. Tell us a little bit about it: How should people interact with it? What do you hope for it to accomplish?

People can access the dashboard now at JustAir.app. Right now you will see just Detroit and Grand Rapids, but we’ll have a few more coming in in the next couple of weeks. Our hope is to bring together all of the different monitoring organizations and folks that are doing this work into one portal so that we all have access to the data and are able to share those insights.

We built this public dashboard to try to be as easy as possible to read. The goal is for you to know in real time what the air quality is closest to you. JustAir exists because there are so many gaps within data around air quality monitoring, depending on how far you are from a monitor. And so 1) you’re able to see that in real time and 2) you’re alerted when air quality may be unhealthy for you, and you may need to alter your planning for the day to help mitigate your exposure. We are raising awareness and also sharing instructions on what you can do to protect yourself and your family.

When people come to the dashboard and are concerned about the air quality around their home, what steps can they take?

In the environmental justice community, if you say the world is on fire, make sure people have a fire extinguisher. We want to make sure that people have the tools to protect themselves.

Moderate air quality is fine unless you’re severely sick and have some of these underlying illnesses. Be thoughtful about it, but typically, we fluctuate between moderate and good air quality every day.

When it hits unhealthy, we give people tips, like, hey, if you can afford it, roll your windows up and put your AC on. Maybe limit your exercise outside today around this affected area. This may be a good time to change your filters because outdoor air quality influences your indoor air quality. And those are important things.

We’re now accustomed to wearing masks because of COVID, but people wear N95s all the time in Mexico and other countries because of the pollution. Maybe throw on a mask as you go about your day-to-day and limit your exposure.

We give tools and tips, near-term things, but also long-term things: go support your local plant or flower store and get some plants in your home. These are the things that we try to inform residents on what they can do to take control over the issue that they may not have control over.

What are your goals and next steps for the dashboard?

Right now, we’re tightening up our text messaging. You can try it right now on the signup page. When you sign up with your name, email, etc., you’ll start receiving texts. We want to get to a point where community members can go to a link and type in their phone number and see the stats for their zip code: to see how many alerts they received, things that are happening in our communities, and recommendations. Almost like a personal air quality report card for you.

We pride ourselves on trying to distill the information in our analytic insights. It’s a lot of data, you can imagine. I’m pulling readings at almost one- to five-minute intervals. How do we take that data and derive what are the causes for these anomalies, and what are the solutions that could come about? For example, if I see a pollutant like NO2 spiking at 3 pm by a school every weekday, that tells me something. Maybe parents or school buses are idling when they pick up their children. Going through the data and just thinking creatively through the weird anomalies and asking what could be happening there. We can automate that process, and it’s going to be exciting. That gets us closer again to decision-making and solutions versus spending a lot of time looking through hundreds of thousands of rows of data.

As a co-chair of the data monitoring working group for the air quality collaborative in Wayne County & Detroit, what do you hope to accomplish?

Collaboration is so important. There’s unique issues that happen at a community level that we may not share with other communities. For example, southwest Detroit may have certain pollutants, versus the east side of Detroit, which will have different issues that have to do with Stellantis [the Stellantis Jefferson North Assembly Plant, which designs, engineers, manufactures, and markets Chrysler, Jeep, and Dodge brand vehicles].

I’m excited about the collaboration, sharing knowledge, sharing resources, and sharing insight so that we can learn from each other and accelerate the way we do our work more effectively.

Second thing is that I’m excited to collectively own this work. JustAir, we’re just a small piece of it. With my background, I’m fortunate enough to be able to know what the realm of the possible is from a technical side, but what I am very ignorant of, even having family members and history of members who have done community work and civil rights, I’ve never done community work. Learning from folks like Donele Wilkins [director of Green Door Initiative] and other folks in Detroit working for environmental justice and other community leaders in my city means that I’m understanding how to develop those skill sets and how to do this work the right way. As a collaboration, we can call this work our work, and be an example that all cities can replicate.

[The collaborative recently released a report, From Air Pollution to Solutions: Collaborative Planning for Air Quality in Detroit and Wayne County, outlining plans to use monitors, data, and outreach to advocate for the right to clean air.]

What's your vision for air quality justice?

The fundamental view that I have of the world is this: your quality of life and your ability to enjoy this life shouldn’t be determined by your skin color or where you were born. Pretty simple.

When I think about the vision for JustAir and justice in general, that’s Detroit. But beyond is just that. You walk out your door and can enjoy the same quality of air and not have to struggle with certain illnesses that another part of the community does not have because they are not overburdened with air quality issues and trucking traffic.

What we’re looking at is equity. All communities within a city context, county context, wherever you want to slice it, should have equal access. That’s our goal: to hopefully not exist. You solve the problem, and you don’t need JustAir anymore.

What is the pathway forward for JustAir in Detroit and beyond?

Where we’re at now is creating awareness. What makes us have different conversations around things like policy, punitive impact law, anti-highway ordinances, trucking traffic ordinances, rezoning industrial space, and residential space? With data available, we can now have these conversations and raise awareness among community members to say this should be a priority. We can’t fight for what we don’t know. It’s so important for community members to have data access support. When they go vote, or when they go share the issues that they want addressed in their community, there’s something they can actually speak to. That’s number one.

Number two, climbing the tree, is environmental change. For example, using our data to plan tree canopies. I’ve had conversations in Grand Rapids about using our data to think about truck rerouting and changing the environment from that perspective. To say, “Hey, we should prioritize electrification of school buses in this community because they’re overburdened versus this other community.” How do we be more efficient with our resources to make sure those who need it most get it first?

And then lastly, I would say the North Star is policy change. Right now, we live in an environment in many states where we’re prioritizing business over looking at the cumulative impact of issues like air quality. I’ll look at a factory that wants to go into my community. As long as you pass code, we’re not looking at how full that bowl is before we put more water into it, more pollution.

When we start looking at the perspective of the community first, we can make policies around that. It’s going to be exciting to not just make policies but to make sure that they’re enforceable and actually incentivizing the right actors, so we can help mitigate their risk. So kids and residents can work, play, and have fun, and have the life they deserve.

Last, what can individuals and organizations do to support clean air in our communities?

If I could say one thing, it would be just spread the word, raise awareness. I go to my barber and we talk about the Air Quality Index. That’s a good opportunity and space to share that. You don’t know who’s listening, hearing, or learning. In those spaces of community, share the things that you care about.

We often times carry our problems, but your neighbor is probably going through the same thing. Find opportunities and time in those spaces to share what’s important to you and educate folks around you.

Power is always with the many voices. The more we have people with that microphone and a real echo chamber behind equal access and air quality equity, the better chance we have at creating a better life.

If you are an outsider or organization wanting to help, remember that power rests in the community, and the community should be driving this work. Make sure that you are listening actively, make sure that you put aside your priorities and listen to the priorities of the community. They know what’s best for their families, and we just want to be a support.