Sample Collection

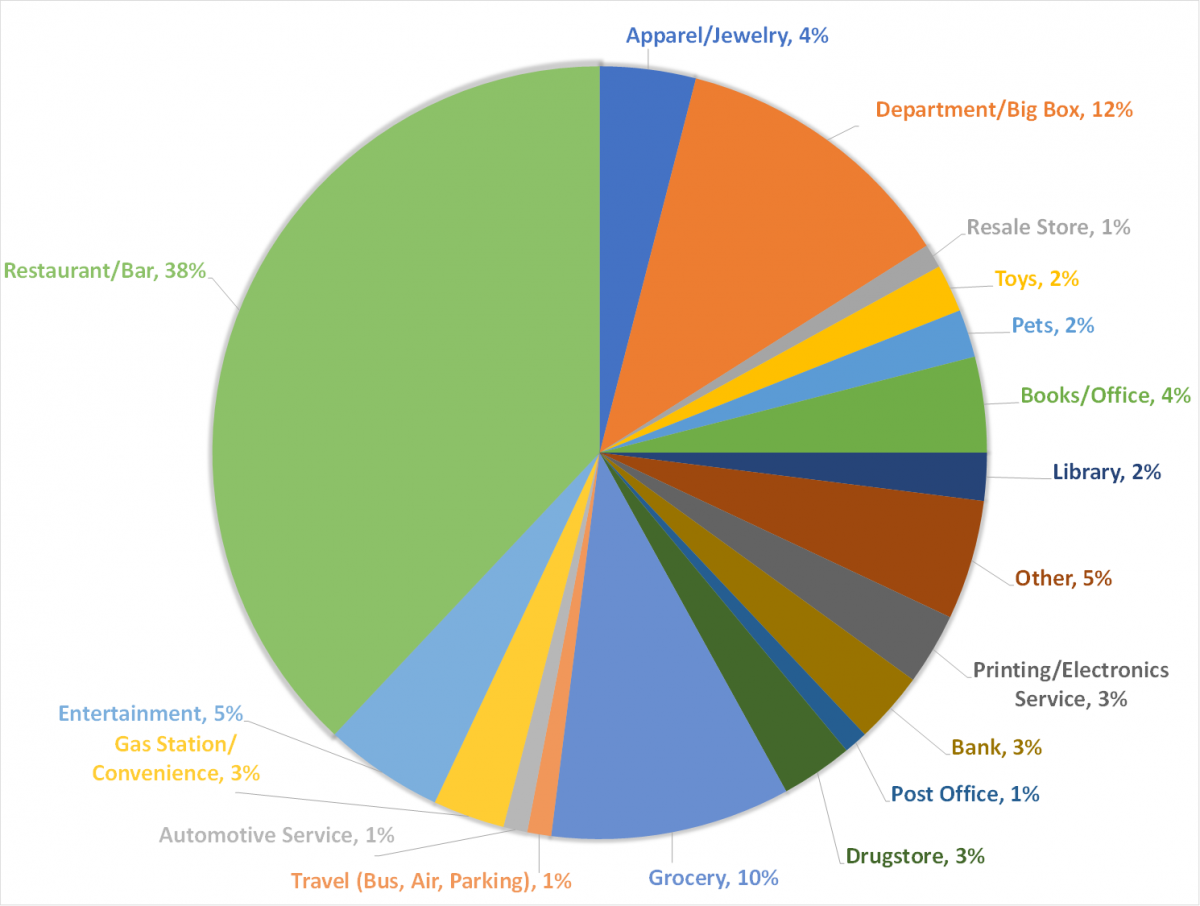

Paper receipts were collected using a citizen science approach from consumers in southeast Michigan from January to April 2017. Consumers were instructed to fold receipts with printed side in and place in a paper envelope. The collected receipts were printed in 2016 and 2017 and originated from eight U.S. states with the large majority from southeast Michigan. While not exhaustive of all possible businesses and entities that use thermal paper, the receipts in this study represent a wide range of retailers and service providers. The breakdown of business types is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Percentage of receipts collected from each business category

Among the 208 receipts, we received 41 replicate receipts from 39 unique businesses locations. (For example, we received three receipts from a local favorite, Zingerman’s Delicatessen, on 422 Detroit Street in Ann Arbor, MI.) Our analysis determined most of these replicate receipts contained the same developer chemical. To avoid skewing statistics, we removed redundant receipts from the data set. This resulted in 167 samples. Only two (TCAUP Media and The Raven’s Club) had disparate results, namely one receipt from the same business location had BPS and the other had BPA, and these results were preserved in the data set.

Receipts collected from different locations of the same store were preserved in the data set.

Instrumental Analysis

Receipts were wiped with a dry Kimwipe to remove dust from the surface. Developer chemicals are abundant on thermal receipt paper, so this dry wiping did not affect our ability to detect BPA, BPS or other developer compounds.

Next, a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS5 Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometer was used in attenuated total reflection (ATR) mode with a diamond crystal. Each receipt was placed with the printed side on the ATR sample stage and a spectrum was obtained from 4000-450 cm-1. For some receipts, a spectrum was also obtained from the back side to verify the absence of thermal coating chemicals on that side.

To avoid cross-contamination, the ATR stage was thoroughly cleaned with isopropyl alcohol after each spectrum was obtained.

The resulting infrared spectra were analyzed visually and compared against a library of known spectra to detect the presence of developer chemicals on the printed side of each receipt. FTIR is a widely used tool for determining the chemical identity of compounds.

Our spectral library included BPA and BPS. We visually examined the BPA and BPS spectra to identify bands unique to each chemical to avoid misidentification.

The developer chemical known as Pergafast 201 was not in the library. We determined the presence of this chemical by noting spectral similarities with related compounds (with sulfonate and sulfonamide groups in particular) that were in the library and comparing those findings to the molecular structures of developer chemicals, including Pergafast 201, known to be used in thermal receipts (U.S. EPA 2014). Our determination of Pergafast 201 should be verified in future work using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry.

Receipts with no coating--in other words, that were not thermal paper--showed the characteristic spectrum of plain paper.

Collected infrared spectra that did not match the unique bands of plain paper, BPA, BPS, or the chemical we identified as Pergafast 201 were marked “inconclusive.”

Figure 3. Receipt undergoing ATR-FTIR testing.

Method Validation

Four thermal paper samples from our study were tested by a third-party lab, TÜV Rheinland, using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC/MS) for BPA and BPS. TÜV Rheinland of North America is accredited as a Nationally Recognized Testing Laboratory (NRTL) by OSHA, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, in the United States.

According to our FTIR analysis, one of these samples contained significant BPA, one contained significant BPS, one contained an undetermined developer, and one was uncoated. The GC/MS analysis corroborated the FTIR results for all four samples. Details are in the Findings section.